To truly understand olive oil, we have to go back. Way back. We're not talking centuries, but thousands of years, to the very dawn of agriculture itself. This "liquid gold" wasn't a sudden discovery; it evolved right alongside the earliest human settlements in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Neolithic period. Long before anyone was writing things down, our ancestors had already figured out how to cultivate wild olives and press them for their precious oil.

Tracing the First Drops to the Neolithic Age

The story of olive oil begins in the ancient lands of the Levant—the region we now know as Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, and Jordan. This area wasn't just a cradle of civilization; it was the home of the wild olive tree, Olea europaea, one of its most essential natural treasures.

Even before great empires rose and fell, the people living here saw the potential locked inside the bitter, inedible fruit of the wild olive. Getting to that potential wasn't as simple as picking a piece of fruit from a branch. It required real ingenuity. These early communities developed the first rudimentary technologies to transform something they couldn't eat into a vital source of fat, fuel, and even medicine. This was a fundamental shift in our relationship with the world around us.

The First Clues of Cultivation

How do we know all this? Archaeologists have pieced the story together from fascinating clues left behind. Ancient olive pits, fragments of olive wood, and primitive stone tools all paint a vivid picture of how our ancestors took the first steps toward domesticating the olive. These aren't just old artifacts; they are records written in stone and seed, proving that humans were actively cultivating trees, not just foraging for wild fruit.

This transition from gathering to cultivation was a true game-changer. It meant communities could count on a more stable and plentiful supply of olives, paving the way for organized production. Key evidence supporting this early history includes:

- Ancient Olive Pits: Excavated pits from thousands of years ago reveal a clear evolution from smaller, wild olive types to the larger, cultivated varieties we recognize today.

- Primitive Stone Presses: Archaeologists have found simple but effective stone tools across ancient settlement sites, clearly designed for one purpose: crushing olives.

- Pollen Analysis: By studying sediment cores, scientists can analyze ancient olive pollen. This helps them literally map the spread of olive groves over millennia, confirming just how widespread cultivation became.

This evidence makes it clear that the origin of olive oil is deeply intertwined with the agricultural revolution. We can see this practice taking root as far back as the Neolithic period, somewhere between 8300 and 4500 BCE. By 6000 BCE, we have solid proof of olive cultivation in Palestine, and from there, it spread to Crete by 2500 BCE. For a deeper dive into this timeline, the history of olive oil's beginnings on Enjoy Mediterranean is a great resource.

The domestication of the olive tree wasn't just about farming. It was a cultural turning point. By figuring out how to extract the oil, early humans created something that would become a cornerstone of diet, economy, and ritual for countless civilizations.

This wasn't a fast process. It took generations of patient observation and careful selection to breed trees that produced bigger, oilier fruit. You could think of it as humanity's very first agricultural research project, one that spanned thousands of years. The result was a hardy tree perfectly suited to the rocky Mediterranean soil and a product that would go on to fuel empires and define the entire region’s culture and cuisine.

How the Minoans Built the First Olive Oil Empires

While people had been pressing olives since the Neolithic Age, it was the Minoan civilization on Crete that really saw its potential. They didn't just see a food source; they saw the engine for an empire. Flourishing in the Bronze Age, the Minoans were more than just incredible artists and sailors—they were the world’s first olive oil tycoons. They were the ones who began systematically planting vast olive groves, building a powerful, centralized economy around what we now call "liquid gold."

The Minoans didn't just grow olives; they mastered the entire operation from grove to market. Their society was built around grand palaces, like the legendary one at Knossos. These weren't simply royal homes; they were buzzing administrative and economic centers. Digging through the ruins, archaeologists have found maze-like storage rooms packed with enormous ceramic jars called pithoi. Some were big enough for a person to hide in, all designed to hold incredible amounts of olive oil.

This wasn't just squirreling away food for a rainy day. It was a highly organized system. The palace controlled the collection, storage, and distribution of the oil, and every last drop was recorded on clay tablets in the Minoan script, Linear A. This level of detail tells us they weren't just thinking about feeding themselves. They were building wealth through international trade.

The Trade Routes of Liquid Gold

With their advanced ships, the Minoans exported their most valuable product across the Aegean Sea and far beyond. Their vessels, heavy with jars of olive oil, sailed to mainland Greece, Egypt, and the Levant. This trade established Crete as a dominant economic force, generating the immense wealth needed to build their magnificent palaces and paint their famous, vibrant frescoes.

It's easy to see why olive oil was such a hot commodity. In the ancient world, it was used for everything:

- A Culinary Staple: It was a primary source of fat and a cornerstone of the Mediterranean diet, even thousands of years ago.

- Fuel for Light: Long after the sun went down, olive oil lamps lit up homes and palaces.

- An Essential Ointment: People used it for personal hygiene, as a base for perfumes and cosmetics, and for all sorts of medicinal remedies.

This incredible versatility made olive oil a product everyone needed, and the Minoans were perfectly placed to supply it.

Mycenaean Heirs to the Olive Oil Throne

When the Mycenaean civilization took center stage on mainland Greece around 1600 BCE, they didn't reinvent the wheel. Instead, they took the Minoan model and ran with it. The Mycenaeans, famous for their mighty fortified citadels like Mycenae and Pylos, immediately recognized the power held within the humble olive. They took over the Minoan trade routes and continued the large-scale cultivation and export of oil.

We have an astonishingly clear picture of their operations because we can actually read their script, Linear B. Thousands of clay tablets discovered in Mycenaean palaces detail the production and movement of olive oil with painstaking precision. They record the yields of specific groves, the oil rations given to workers, and even the amounts set aside for offerings to the gods.

These meticulous Linear B tablets show that olive oil was far more than just a product—it was a form of currency. The entire palace economy literally ran on oil. It was used to pay laborers, supply soldiers on campaign, and trade for other vital goods like metals and luxury items.

The legacy of these two Bronze Age cultures is unmistakable. The Minoans laid the foundation, turning olive oil into a systematically produced and traded commodity. The Mycenaeans then scaled it up, embedding oil even deeper into their economic and administrative life. Together, they set a pattern that would echo for centuries, proving that in the ancient Mediterranean, controlling the olive tree meant controlling wealth and power. The origin of olive oil as a major economic force can be traced right back to them.

The Greek Expansion of Olive Oil Culture

While Bronze Age civilizations certainly saw the economic power of olive oil, it was the Ancient Greeks who wove it into the very fabric of their society. For the Greeks, especially the Athenians, the olive tree wasn't just another crop. It was a divine gift, a symbol of their identity that touched every part of daily life. The origin of olive oil as a cultural cornerstone truly begins with them.

The legendary founding of Athens itself hinges on this sacred tree. As the story goes, the city needed a patron deity, and the competition was between Poseidon, god of the sea, and Athena, goddess of wisdom. Poseidon struck the Acropolis with his trident and a saltwater spring appeared. Athena, in turn, simply planted the first olive tree. The people chose her gift, recognizing it as a promise of peace, food, and prosperity. From that moment on, the olive tree was inseparable from the Athenian soul.

An olive branch became the ultimate symbol of peace and victory. Winners at the ancient Olympic Games weren't crowned with gold but with a simple wreath of olive leaves—a prize considered far more honorable. This tells you everything you need to know about how deeply the olive was revered in the Hellenic world.

This sacred bond was more than just mythology; it drove a very practical and widespread dedication to olive cultivation. Solon, the celebrated Athenian statesman, passed laws in the 6th century BCE to protect olive groves. He made it illegal to cut down more than two trees in any grove per year, a clear sign of the tree’s immense economic and cultural worth.

Spreading Olive Groves Across the Sea

When the Greek city-states began founding colonies across the Mediterranean between the 8th and 6th centuries BCE, they brought more than just soldiers and stonemasons. They brought their most cherished plant: the olive tree. This wasn't just a whim; it was a deliberate act of cultural and agricultural expansion. Planting an olive grove was like planting a flag. It showed a long-term commitment to a new land, turning a foreign landscape into something familiar and Greek.

This expansion had a profound, lasting impact. The Greeks introduced their advanced farming techniques to new regions, most notably Southern Italy and Sicily—an area they called Magna Graecia, or "Great Greece." These new groves thrived, transforming uncultivated lands into major hubs for olive oil production. The process was straightforward but incredibly effective:

- Smart Site Selection: Colonists picked locations with climates and soil that mimicked their homeland, giving the trees the best chance to flourish.

- Bringing the Best: They carried cuttings from their most sacred and productive trees, ensuring the new groves would maintain their high quality.

- Sharing the Knowledge: They passed on their expertise in pruning, harvesting, and pressing, establishing a tradition of excellence that has endured for millennia.

This methodical spread permanently reshaped the agricultural map of the Mediterranean. It's the reason places like Southern Italy are still famous for their olive oil—a legacy that started with Greek colonists over 2,500 years ago.

The Amphora Economy

The Greeks didn't just grow olives; they mastered the art of trading the oil. Their iconic clay jars, known as amphorae, were the shipping containers of the ancient world. Each one was ingeniously designed for transport on ships, with a pointed base that could be wedged into sand or stacked tightly in a ship's hold.

This system fueled a massive and highly organized export business. Thanks to incredible historical records like the Zenon Papyri from 3rd century BCE Egypt, we have a clear picture of just how huge this trade was. These documents detail specific shipments, listing hundreds of jars from city-states like Miletus and Samos. One cargo manifest, for instance, logged 101 small jars and 255 large jars of oil from Miletus alone.

Such records prove that Greek olive oil was a major commodity that drove economic growth and international clout. You can discover more insights about these large-scale trade operations on uwlabyrinth.uwaterloo.ca. Through this sophisticated network, Greek culture and its most essential product reached every corner of the known world.

Rome's Industrial Revolution in Olive Oil

If the Greeks made olive oil a cultural treasure, it was the Romans who turned it into a full-blown industry. The Roman Empire’s incredible appetite for this liquid gold kicked off an ancient industrial revolution, scaling production to a level the world had never seen. For Rome, olive oil wasn't just a food or a cultural item; it was a strategic asset, essential for fueling their legions, cities, and vast economy.

This was a major shift. Olive oil went from being a precious commodity to a mass-produced necessity, and the Romans, with their signature logistical genius, were the ones to make it happen. They quickly realized that to supply a city of a million people, the old, slow methods of pressing olives just wouldn't cut it. They needed machinery.

Engineering an Oil Boom

Roman engineers developed advanced mechanical presses that were the ancient equivalent of modern factory equipment. Two key innovations, the trapetum and the mola molearia, completely changed the game. These devices used heavy stone wheels, complex levers, and counterweights to crush olives and press the paste, extracting far more oil with much less manual labor.

Think of it as the difference between using a small hand-cranked juicer and a massive industrial hydraulic press. The output was on a totally different scale. This technological leap allowed for huge, specialized production facilities, especially in provinces like Hispania (modern Spain) and North Africa, which became the olive oil powerhouses of the ancient world.

At the height of the Empire, between 200 BCE and 200 CE, this industrial production hit staggering numbers. The province of Tripolitania was pumping out around 30 million liters a year, while Byzacena produced an incredible 40 million liters. Over a 260-year period, Rome itself imported an estimated 6.5 billion liters of olive oil—a figure that speaks volumes about their logistical mastery. You can explore the details of Rome's massive trade volume to get a sense of the scale.

The Roman approach to extraction laid the groundwork for the methods we still use today. While they perfected mass production, modern techniques have continued to refine the process for quality.

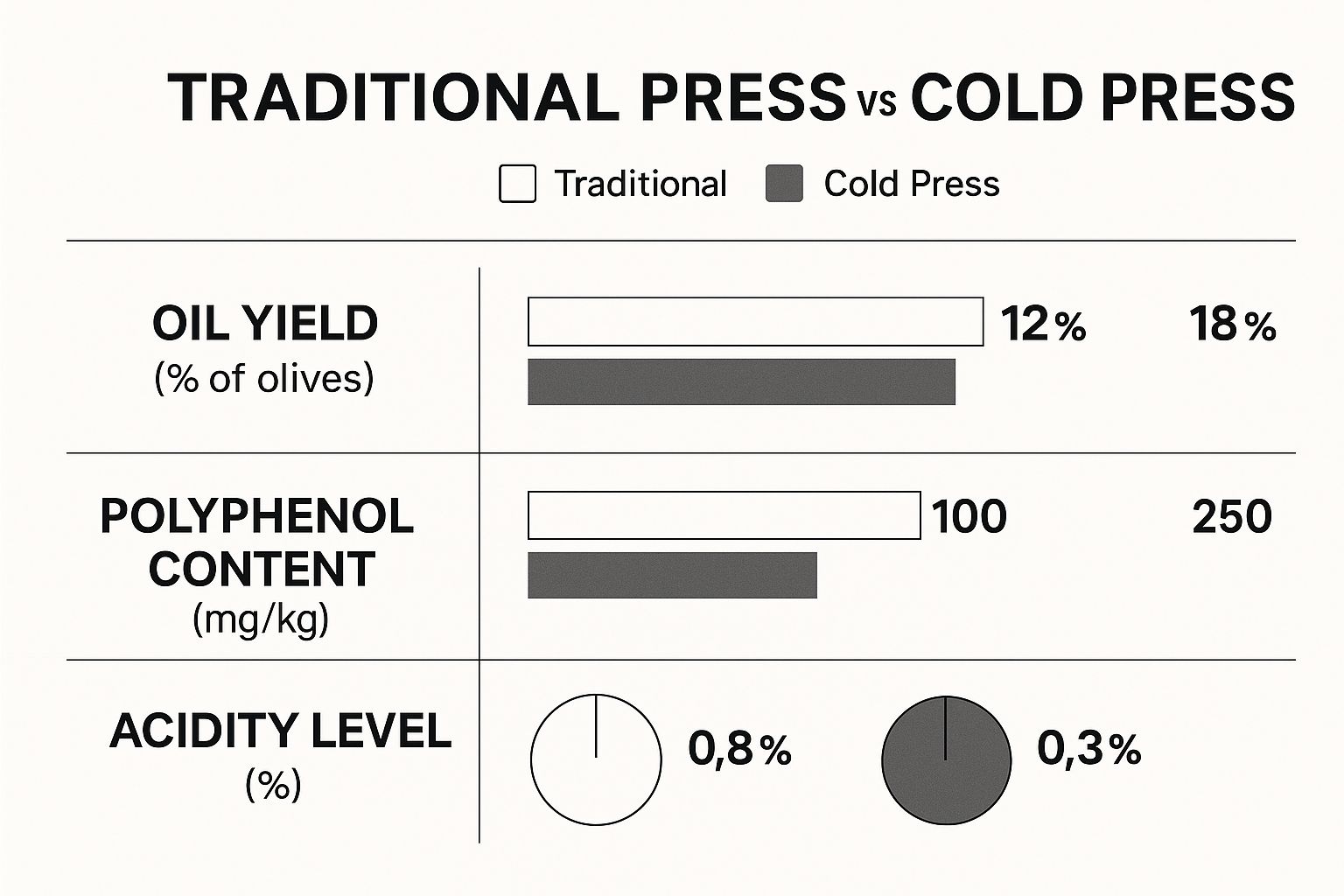

This image compares a traditional press—an evolution of Roman technology—with modern cold-press methods. It’s clear how today’s techniques yield more oil with lower acidity and higher polyphenol content, preserving the very best of the olive's flavor and health benefits.

To understand just how revolutionary the Roman approach was, it helps to see their methods side-by-side with what came before. This table illustrates the leap in technology that made their industrial-scale production possible.

Ancient Olive Oil Production Methods: A Comparison

| Era / Civilization | Primary Extraction Method | Description | Efficiency Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minoan / Early Greek | Treading & Bag Press | Olives were crushed by foot or with simple stone rollers, then the paste was placed in bags and squeezed by hand or with weighted levers. | Very Low |

| Classical Greek | Lever & Fulcrum Press | A long wooden beam, weighted with stones or a winch, was used to press down on woven baskets filled with olive paste. | Low to Moderate |

| Roman Empire | Trapetum & Mola Molearia | Large, gear-like stone basins with heavy millstones crushed olives. The resulting paste was then pressed with sophisticated screw and counterweight presses. | High |

| Roman Empire | Screw Press (Cochlea) | A major advancement using a large wooden screw to apply immense, continuous pressure to the olive paste, maximizing oil extraction. | Very High |

The Romans didn't just improve on existing ideas; they engineered entirely new systems. The introduction of the screw press, in particular, was a monumental step forward, allowing for a level of efficiency that powered an empire.

The Annona and a Mountain of Evidence

So, how could Rome possibly use that much oil? A huge part of the demand came from the annona, the state-run grain dole that was later expanded to include other essentials like olive oil. For the citizens of Rome, olive oil wasn't just something you bought at the market; it was a right, provided by the state. This massive welfare program created a constant, guaranteed market for provincial producers.

Getting all that oil to the capital required a supply chain of incredible complexity, involving fleets of ships hauling specialized clay jars called amphorae. These weren't just simple pots; they were standardized containers, stamped with information about their origin, producer, and quality—much like a modern shipping label.

Perhaps the most dramatic evidence of this industrial-scale consumption is a man-made hill just outside the ancient city’s walls: Monte Testaccio, or the "Mount of Shards." This isn't a natural landform.

Monte Testaccio is a literal mountain, standing over 115 feet high, built almost entirely from the broken fragments of an estimated 53 million olive oil amphorae discarded in Rome.

This mind-boggling archaeological site is a monument to the sheer volume of olive oil that flowed into the capital. Every single shard tells a story—a journey from a grove in Spain or Africa to a Roman kitchen, lamp, or bathhouse. It’s a powerful, tangible reminder of how Rome's logistical genius and engineering prowess transformed olive oil into the lifeblood of an empire.

Surviving the Middle Ages and Renaissance Revival

When the Western Roman Empire collapsed in the 5th century CE, the massive, organized olive oil trade it had powered for centuries simply disintegrated. The sophisticated shipping lanes and Roman roads that moved millions of clay amphorae across the Mediterranean fell into disrepair. As a result, production didn't just shrink; it became hyper-local, a shadow of its former, continent-spanning self.

For a while, it seemed like the story of olive oil as a major commodity might end there. But the precious liquid, and the skills needed to make it, were far too valuable to disappear entirely. Instead, the tradition was kept alive in quiet corners of society, waiting for the right moment to flourish again.

During this fragmented era, Christian monasteries became unlikely guardians of ancient farming knowledge. Committed to being self-sufficient, monks carefully preserved the Roman techniques for growing olives and pressing the oil. Their groves were more than just farms; they were living libraries, protecting priceless olive tree varieties through the chaos of the early Middle Ages.

An Islamic Golden Age for the Olive

While Europe’s production was scattered, a huge leap forward in olive cultivation was happening on the Iberian Peninsula. After the Islamic conquests of the 8th century, the rulers of Al-Andalus (modern-day Spain and Portugal) didn't just maintain the old Roman groves—they revolutionized them.

Arabic agronomists brought advanced irrigation systems and new grafting methods, which dramatically improved the health and output of the olive trees. They approached olive growing as a science, even writing detailed agricultural manuals. This period was a critical bridge, preserving ancient wisdom while adding new innovations that would eventually help Spain become the olive oil powerhouse it is today.

You can still hear the echoes of this history in the Spanish language. The word for oil, aceite, comes directly from the Arabic al-zait, and the word for olive, aceituna, comes from al-zaytuna. It’s a linguistic fingerprint of this deep agricultural heritage.

These breakthroughs ensured that high-quality olive oil production wasn't just saved but was actively being refined, setting the scene for its big comeback across Europe.

The Renaissance Reignites the Trade

That comeback arrived with the Renaissance. As powerful Italian city-states like Florence, Venice, and Genoa emerged as centers of finance and commerce, they needed valuable products to trade. They found a perfect one right in their own hillsides: olive oil.

Wealthy merchants and nobles began pouring money into agriculture, planting vast new olive groves in regions like Tuscany and Liguria. To them, olive oil was more than just a staple food. It was a luxury good, a clear signal of wealth, status, and refined taste. This change in attitude was everything.

The oils from these Italian regions started earning a reputation across Europe for their incredible quality and distinct flavors. This was the moment the modern idea of terroir really began to apply to olive oil—the concept that a specific place gives a unique character to its food. People started seeking out the peppery kick of a Tuscan oil or the buttery smoothness of one from Liguria.

This newfound appreciation completely changed the game. The trade was no longer just about shipping functional, mass-produced oil for lamps and basic cooking. It was about connoisseurship. Italian merchants leveraged their sprawling trade routes to export these prized oils, re-establishing olive oil as a premium international product and building the foundation for the gourmet market we know and love today.

The Enduring Legacy in Your Kitchen Today

Think about the bottle of olive oil sitting in your kitchen right now. It’s easy to see it as just another cooking staple, but if you pause for a second, you’ll realize it's so much more. That simple bottle is the culmination of an incredible story that began thousands of years ago.

Every part of its journey, from the first wild olive trees tamed in the ancient Levant to the sprawling, efficient groves of the Roman Empire, has led to the oil you use today. The very trade routes carved out by Phoenician and Greek sailors laid the groundwork for our modern global supply chains. The deep cultural respect it earned in antiquity is why we still see it as a cornerstone of both health and exceptional food.

The origin of olive oil isn't just a dusty history lesson; it's a living, breathing legacy that shapes everything from how we grade our oils to the flavors we prize.

Bridging Past and Present

Interestingly, many of today's best producers are looking backward to move forward. They are on a mission to find and revive ancient olive cultivars, some of which were nearly forgotten. These older varieties often possess a unique hardiness and offer wonderfully complex flavors you just can't find anywhere else.

There’s also a real back-to-the-land movement happening. More and more growers are embracing sustainable farming techniques that feel remarkably similar to ancient methods. It's a philosophy that respects the earth and values quality over sheer quantity, much like the farmers of old who treated their groves as a sacred trust.

Every drop of olive oil is a taste of history. It's a connection to millennia of human culture, innovation, and commerce, bottled for your kitchen.

This is what makes a simple ingredient feel so profound. It carries the echoes of Minoan feasts, the triumphs of Greek athletes, and the ingenuity of Roman engineering. So, when you learn how to choose the best olive oil, you’re doing more than just shopping—you’re participating in a tradition that has helped build civilizations.

The next time you drizzle it over a salad or add it to a hot pan, take a moment. You’re not just cooking. You’re partaking in history.

A Few More Questions About Olive Oil's Origins

Let's dig into some of the most common questions people have about where olive oil comes from. Think of this as tying up a few loose ends to give you the full picture.

Where Did Olive Oil Truly Come From?

The story of olive oil begins in the ancient Near East, in the area we now know as the Levant. This region, covering modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan, is the native home of the wild olive tree. The earliest archaeological clues point to humans cultivating these trees and pressing their fruit for oil as far back as 8,000 years ago.

This wasn't an overnight discovery. It was a slow, deliberate process where early farming communities figured out how to domesticate the wild olive. Over generations, they bred trees that yielded larger, more oil-rich fruit, setting the stage for every great civilization that would come to rely on this liquid gold.

How Different Was Ancient Olive Oil from What We Use Now?

If you could taste olive oil from thousands of years ago, you'd be in for a surprise. It was a world away from the smooth extra virgin oils we have today. The flavor was likely much stronger, even harsh, and the texture would have been thick and gritty.

The main culprits were the production methods and a total lack of filtration.

- Extraction: The first methods were incredibly simple—think treading olives with bare feet or using basic stone beam presses. These techniques just couldn't separate the oil from the fruit's water and solids very well.

- Acidity: It took a long time to get the olives from the tree to the press. This delay caused the fruit to oxidize, leading to much higher acidity levels and a sharp, sometimes unpleasant, taste.

- Purity: Ancient oil was almost always unfiltered. It would have looked cloudy and contained tiny bits of olive flesh and pit, making it feel coarse in the mouth.

Really, ancient oil was more about function than flavor. It was a vital source of calories and a versatile tool, not a gourmet ingredient.

Which Culture First Became the Masters of the Olive Oil Trade?

While plenty of ancient peoples produced olive oil, it was the Minoans on the island of Crete who first turned it into a real commercial enterprise around 2500 BCE. They were the original olive oil moguls, building their entire economy around cultivating, storing, and exporting the precious liquid.

Their genius wasn't just in growing olives; it was in creating an entire system. The Minoans used enormous clay jars called pithoi for mass storage and developed standardized smaller amphorae for shipping. This innovation created the very first large-scale olive oil trade network across the Mediterranean.

The Mycenaeans and later the Greeks certainly expanded on this foundation, but it was the Minoans who wrote the original playbook for making olive oil a cornerstone of international commerce.

At Learn Olive Oil, we believe that knowing the incredible story behind this liquid gold makes every drop more meaningful. We offer expert-led resources to help you explore the world of premium olive oil, from tasting like an expert to finding the perfect bottle for your pantry.

Leave a comment